An imaginary story

Once upon a time there was a place where diarrhea was one of the main killers of young children. Most treatment was home remedies or treatment from traditional healers or “quacks,” i.e., those without recognized medical qualifications. It wasn’t that families felt these options were superior to what was offered by a medically qualified health worker, but they were cheaper and more accessible.

So, faced with this situation, the child health people devised a new plan to overcome child diarrhea, the Skilled Diarrhea Treatment Provider strategy. And they decided to track performance with a Skilled Diarrhea Treatment Provider coverage indicator (SDTP), measured using household surveys. For identified diarrhea cases, parents were asked what credentials they thought the person treating the diarrhea had. If they answered physician, nurse, health assistant, or pharmacist, that was considered “skilled” and would go into the numerator of their SDTP indicator. This was the case even if all they gave was an antibiotic, say metronidazole—the wrong treatment.

But if the treatment was from a traditional healer or a quack, that wouldn’t count, even if what was given was oral rehydration solution and zinc—the right treatment.

Now let’s say there was a big increase in SDTP coverage. What mortality effect would we expect?

The true story

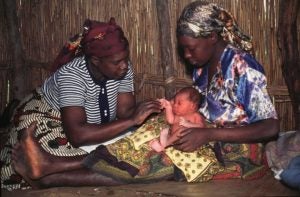

Twenty years ago, in many settings there was very high maternal and newborn mortality from causes that, in principle, could be successfully treated. In many of these situations, births were at home, attended by traditional birth attendants (TBAs). It wasn’t that families felt these were superior to what was offered by a medically qualified health worker, but they were more accessible and that was what people were accustomed to.

So, faced with this situation, the safe-motherhood people devised a new strategy to handle these maternal and newborn complications, the Skilled Birth Attendance strategy. And they decided to track performance with a Skilled Birth Attendance coverage indicator (SBA), measured using household surveys. For births, women were asked what credentials they thought the person attending the delivery had. If they answered physician, nurse, or midwife, that was considered “skilled” and would go into the numerator of the SBA indicator. This was the case even if they gave medically non-indicated, risk-increasing care.

But if the treatment was from a TBA or some other category of worker considered unsuitable, that wouldn’t count, even if highly appropriate treatment was given, say, oxytocin after delivery to prevent post-partum hemorrhage or mouth-to-mouth resuscitation for a non-breathing newborn.

In many places, there were big increases in SBA coverage, meaning—in many instances—care had shifted from TBAs to supposedly qualified practitioners. What mortality effect have we actually seen? Let me give a few examples:

- About two years ago, I did an analysis of Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data for the 18 countries with the highest maternal and newborn mortality burden for which SBA and neonatal mortality rate (NMR) results were available from at least two surveys. I looked at the correlation between changes in SBA delivery rates and in NMR. What I found was a moderate negative correlation, i.e., the bigger the increase in SBA rates, the smaller the decline in NMR (Pearson’s r=-.33). This is not what one would expect if SBA deliveries mean significantly better care and better outcomes.

- In the most recent DHS from Nigeria (2013), we see huge diversity across states. In some states, over 90% of births are attended by a TBA; in other states, over 90% of births are attended by an “SBA.” If SBA delivery really means better care and better outcomes, one would expect correspondingly big differences in risk of newborn death. But what does the DHS show? It shows the same levels of mortality in states with very low and very high SBA rates: NMR in the high 30s or low 40s per 1000 births.

- In India, with the Janani Suraksha Yojana conditional cash transfer scheme to encourage institutional births, over the past decade there has been a very big increase in “SBA coverage,” but no corresponding drop in maternal and perinatal mortality.

What lessons can we draw?

- Lesson 1: Supposed credentials have little relation to actual care given.

- Lesson 2: Simply labeling your indicator so that it exactly corresponds to the name of your strategy and then claiming success when your indicator tells you you’re reaching high “coverage” may keep some folks happy, but it doesn’t necessarily drive down the burden of preventable deaths.

In the real world, by the way, the child health people never did have a Skilled Diarrhea Treatment Provider strategy or a corresponding coverage indicator. Instead, they focused on increasing the proportion of cases that get proper treatment (ORS, zinc) and used these as their measures of program performance.

Perhaps for labor and delivery care, we should be taking a leaf from their book. Rather than focusing on who’s there and where it’s happening, how about instead we pay more attention to what’s being done and when?

This post has been lightly edited from its original appearance on the Healthy Newborn Network.