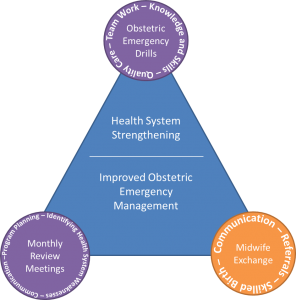

This post is the first of four, which will discuss three interventions that worked synergistically to strengthen a health system and improve obstetric emergency management in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Hospital leaders and the Ethiopian Ministry of Health recognized a complicated problem in obstetric care in Addis Ababa. Primary health centers saw few patients and referred many unnecessarily to overcrowded tertiary hospitals. To help fix the problem, they created a midwife exchange program.

The Maternal Health Task Force supported the midwife exchange program, which was piloted in the St. Paul’s referral network, made up of St. Paul’s Hospital, a tertiary hospital, and eight health centers. Experienced midwives from St. Paul’s Hospital worked shifts in health centers in exchange for midwives from health centers working shifts at St. Paul’s Hospital. The program offered health center midwives opportunities to improve their skills, exposure and comfort level with obstetric emergencies and, in turn, better distribute the burden of obstetric cases within the referral network.

“The health center midwives see obstetric emergencies in books, or in videos, but cannot actually recognize and manage them. We complain a lot because they refer many simple cases to our hospital and we can’t manage that. We don’t have all the beds, the economics,” said Michael Alenayehu, a midwife from St. Paul’s hospital.

Alenayehu’s perception was reality: midwives in health centers don’t often have the opportunity to manage obstetric emergencies during their schooling and are left unprepared when faced with complications or emergencies in health centers. Without the proper skills, the midwife will refer any patient with a suspected complication on to the hospital. Prior to the exchange, referrals occurred without any coordination with St. Paul’s. Referred women were often turned away from an overburdened St. Paul’s and sent from facility to facility, in search of an available bed and the care they needed, even though the majority of these women should be managed at the health center level.

The midwife exchange provided opportunities for building skills and gaining knowledge for the management of obstetric emergencies. Midwives at the health center level are not often exposed to obstetric emergencies, since they are relatively rare. With time at St. Paul’s Hospital, health center midwives were able to attend many high-risk deliveries, increasing their familiarity and comfort with recognizing and managing obstetric emergencies.

“It’s very helpful for the midwifes from the health centers—who are delivering probably very few patients and not used to seeing complicated cases—coming to hospital and seeing lots of eclampsia, anemia, postpartum hemorrhage and other cases and see, for instance, how magnesium sulfate is administered. And when our midwives [from St. Paul’s] go to the health centers, they have an opportunity to see how the health centers function. And especially when the experienced midwives are sent to the health centers, they can coach the midwives there. It works only if the most experienced midwives go there,” said Delayehu Bekele, assistant professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology at St. Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College.

Midwives from St. Paul’s have the opportunity to take on more responsibilities when they are at the health center, strengthening their leadership and decision-making skills. “The midwives that regularly work at St. Paul’s were the experts here and could take major responsibility,” said Kedir Adem, a midwife at Selam Health Center.

Through the exchange, strong relationships were built between the health centers and St. Paul’s Hospital staff, mutual understanding and communication increased, and skills and knowledge for managing obstetric complications improved. The combination of improved skills and communication strengthened the referral network between health centers and St. Paul’s Hospital, which shortened the third delay: getting a woman the skilled care she needs once she reaches a facility.

“What we get from this exchange is mutual understanding between St. Paul’s and the Selam Health Center staff. This is very important, especially because when we referred women from here to St. Paul’s, there were many challenges. Now that staff know each other, the mother will get services more easily,” said Adem.

Midwives from St. Paul’s agree. “I feel a strong connection was made, especially in person. They have my number in health centers and they are going to call me and consult me [if there’s a complication] … If they can’t handle it, we are going to tell them that we are OK with the referral,” said Alenayehu.

The midwife exchange helped correct referral problems within the network by building skills and communication. “The exchange improved women’s care . Previously it was very, very difficult to refer the mother from health center to hospital, difficult to contact hospital staff.” said Tensae Habtamu, a midwife at Selam Health Center.

Not only did improved communication ease the referral process, health center midwives who built skills through the exchange can now manage more complex patients, which means fewer patients are referred from health centers to St. Paul’s Hospital. The exchange also initiated a back referrals program, which allows St. Paul’s Hospital to refer low-risk patients to health centers, decreasing the demand on St. Paul’s Hospital and increasing the number of patients in health centers, which provides health center midwives with much needed patient contact to maintain skills. By the end of the project, St. Paul’s Hospital was back referring two to three women a day to health centers.

Challenges

The midwife exchange was not without its challenges, including different pay rates between the hospital and the health centers, different schedules, transportation and staff turnover. “Here, [at St. Paul’s], there is an eight hour shift for the midwives, so they work for eight hours and the following 16 hours they rest. And what they usually do is they work at other private hospitals, additionally,” said Bekele. St. Paul’s eight-hour shifts made it difficult for their midwives to work the health center’s 36-hour shifts, especially since St. Paul’s midwives have other jobs in private hospitals. “So it was a negotiation that whenever [St. Paul’s midwives] have some duties in the private hospitals, the health center staff agreed to cover their duties and to let them go,” said Bekele.

St. Paul’s Hospital covers transportation to and from work for its midwives, but the health centers do not. Without transportation, midwives from the hospital had a difficult time participating in the exchange. Midwives and health system leadership were able to mitigate these barriers through negotiations and compromises for pay and schedules. But other challenges are harder to mitigate.

Staff turnover weakened the progress made by the program. Many experienced midwives, from both St. Paul’s Hospital and the health centers, who were trained in basic emergency obstetric and neonatal care and who participated in obstetric emergency drills, left the public sector for work in the private sector.

Moving Forward

The midwife exchange strengthened skills, improved the referral network and decreased the burden of cases at St. Paul’s Hospital. “We saw change [in the] number of deliveries and staff motivation. Also, staff from health centers who came to St. Paul now understand the challenge posed by unnecessary referrals. Referrals bring overload to the hospital, as mothers who could get care in centers were coming [to the hospital] and those who needed care at the hospital were not getting it. But when the health center midwives came to St. Paul’s, they could see the challenge. So it helped them think twice before they decide on the referrals so that was one of the important achievements, I believe,” said Lia Tadesse, project director of the Maternal and Child Survival Program in Ethiopia.

The midwives who participated in the exchange enjoyed their time and valued the skills and relationships that they built. “Generally, the exchange was very, very nice. But the time is short. One month [for the program] is short…But if you can increase this to two or three months, it [will] Improve mothers’ health,” said Habtamu.