It is well known that women who have a positive experience with family planning (FP) and sexual and reproductive health (SRH) providers and have access to a choice of contraceptives are more likely to begin and continue using them. This means health providers must also have the appropriate knowledge, skills and attitudes to provide information, counseling and clinical services to enable these positive experiences.

Yet data still shows that some women continue to have unintended pregnancies. These are a major driver of unsafe abortions, which hospitalize about 7 million women a year globally and cause 5 to 13 per cent of all maternal deaths. Addressing this gap between what Bearak, Alkema, Kantorova and Casterline call “desires and outcomes” relies on a strong enabling environment, with governments demonstrating leadership in and commitment to high-quality, rights-based sexual and reproductive (SRH) healthcare.

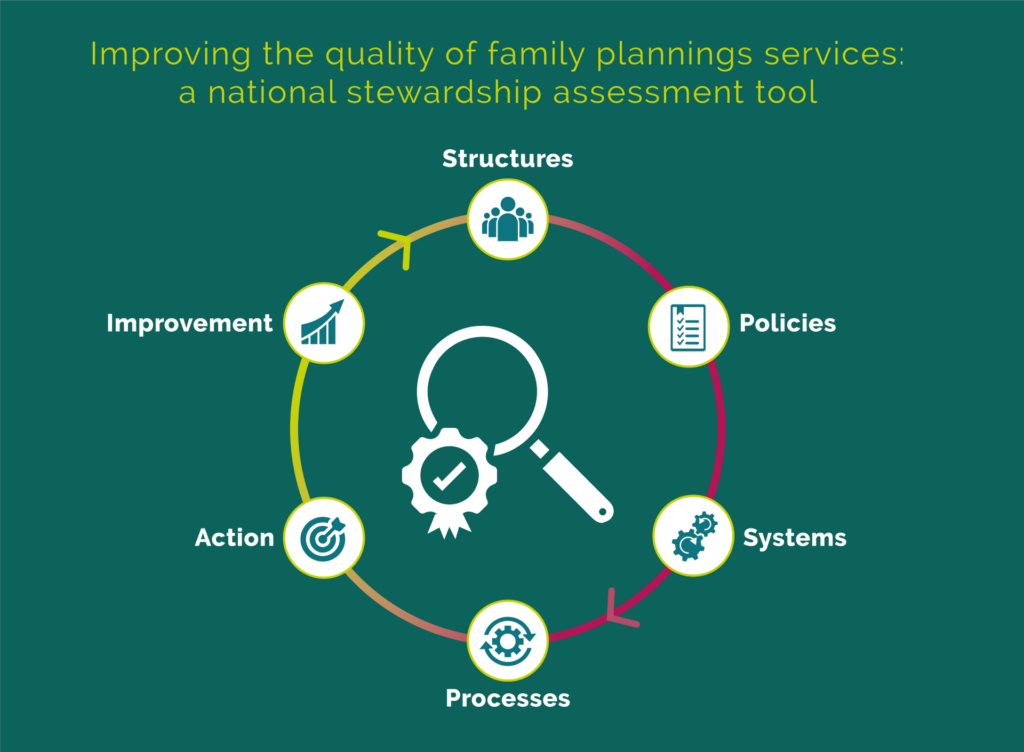

While indicators are routinely collected on service provision and health outcomes, it has been harder to systematically measure the strength of government leadership for improving the quality of SRH and FP services. To help address this gap, under the UK aid funded Women’s Integrated Sexual Health (WISH) programme, worked with governments in seven countries to co-develop an innovative and participatory measurement tool that supports such an assessment. Piloted in 2019, with follow-on assessments conducted in 2021/22, the tool currently covers three domains, which assess:

- Are the necessary structures and policies in place to ensure national stewardship of quality improvements (QI) for FP and SRH services? This could include:

- Focal persons or teams assigned responsibility for leading the development and implementation of QI initiatives

- Government agreed guidelines and standards on the quality of SRH/FP services, such as national technical guidance or supportive supervision guidelines

- Are the necessary processes in place to ensure national stewardship of QI for FP and SRH services? For example:

- Mechanisms for reviewing and validating evidence on the quality of FP and SRH services

- Accessible dashboards populated with relevant and regularly updated FP and SRH indicators

- Supportive supervision and mentorship approaches

- Have actions been taken that drive improvements towards better FP and SRH outcomes? For example:

- Planning and budgeting meetings are informed by current SRH/FP data

- Clinical standards are developed and updated to improve client experiences

- Clients report higher scores of satisfaction with services

- More women report a wider range of FP methods on offer

To date, the tool has been successfully used in seven sub-Saharan African and South Asian countries: Bangladesh, Madagascar, Malawi, Pakistan, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia. Significant improvements have followed implementation:

- A shared vision among health actors and partners about what’s needed to improve the quality of FP/SRH services: In Zambia, the Directorate of Quality Assurance and Quality Improvement and other health partners identified the need to develop a set of reproductive health indicators to track progress towards quality improvement. They then developed a scorecard which enabled them to identify SMART action plans to address the most important bottlenecks, which raised the country’s stewardship score from 33% in September 2019 to 91% in 2021.

- Strengthened government ownership to implement strategies for quality improvement systems: As a result of the assessments, Ministries of Health have seen the need for nominated individuals to drive forward action plans and hold responsibility for improvements. For example, In Punjab province, Pakistan, we worked with the Population Welfare Department, which is responsible for delivering FP services, to establish a QI focal point position and supported this person to coordinate and oversee QI in the province. This included establishing a QI technical working group chaired by both the Population Welfare Department and the Department of Health, which contributed to driving the province’s stewardship score up by 44% over a two-year period.

- Action based on data: The tool has provided a prompt to health management teams to systematically review and analyse data collected through the system and use it to inform their own plans and advocate for necessary resources to implement them. For example, in Busoga District Uganda, the tool spurred increased review of health facility supervision, which in turn informed various budget planning discussions and investment decisions.

The success of the tool is achieved, in part, by bringing together different stakeholders, including national and sub-national governments, service providers and family planning and reproductive health partners to feedback on performance against key indicators. In populating the tool, stakeholders are invited to identify gaps and brainstorm solutions and action plans to address areas of weakness. The aggregated scores are then validated in a workshop and summarised in a scorecard that is accessible to all participants and can be used in future planning and evaluation exercises. The tool requires notes justifying scores, which supports transparency and consistency as staff turnover and new actors are invited to discussions. We are also exploring opportunities to validate this evidence-based tool with broader women’s health outcomes, particularly around access to and uptake of SRH/FP services.

As our understanding of systems and what drives forward transformational change improve, so too must the tool be adapted. For example, we are currently adapting the tool to focus on and measure equity more strongly. We invite those working in the SRH/FP space to use the tool with their own interventions, make adjustments and give feedback. Driving local leadership with tools like this can help develop and foster sustainable solutions to strengthening reproductive rights and meeting the contraceptive needs of women, an essential part of preventing unintended pregnancies and improving maternal health.