This post is part of the Woman-Centered Universal Health Coverage Series, hosted by the Maternal Health Task Force and USAID|TRAction, which discusses the importance of utilizing a woman-centered agenda to operationalize universal health coverage. To contribute a post, contact Katie Millar.

I spent many of my teenage years living in Malawi, enjoying swimming in beautiful Lake Malawi. Wind on to age 30, and I was struggling to get pregnant. Eventually, following illness, I was diagnosed with schistosomiasis and told that I had probably been infected for a while and that it might be affecting my fertility. So I took praziquantel—the only available drug against the parasite—and soon after I was pregnant.

Today my first born daughter is 10 years old. Whilst the links between urogenital schistosomiasis (also called female genital schistosomiasis), sub-fertility and HIV have become increasingly well-established over my first born daughter’s lifetime, sadly lacking is a combined and robust health system that brings together HIV, sexual, reproductive, maternal health and neglected tropical disease communities to address and scale up treatment for urogenital schistosomiasis.

The global burden of disease

Approximately 200 million people are living with schistosomiasis in Africa. Of the people infected with urogenital schistosomiasis, between 100 and 120 million suffer from urinary and reproductive tract damage, which also impacts the likelihood of HIV co-infection and sub-fertility in general. Typically many adolescent girls and women exhibit several symptoms in their lower genital tract where overt bleeding, unpleasant discharge, general discomfort and pain during sex can lead to low self-esteem, depression and stigma.

Peter Hotez estimates that between 20 million and 150 million girls are affected, possibly making it one of the most common gynaecological conditions in sub-Saharan Africa, but, unfortunately, much under-reported. Urogenital schistosomiasis, as in my experience, also affects fertility and may reduce a woman’s reproductive health capacity by up to 75%.

The links between urogenital schistosomiasis in women and HIV are well established. Writing in the Lancet, Stoever and colleagues argue that up to 75% of girls and women infected with female genital schistosomiasis develop often irreversible lesions in the vulva, vagina, cervix, and uterus – creating a lasting entry point for HIV. This results in a threefold increase of HIV infection for women with female genital schistosomiasis.

Gender, equity and rights

There is remarkable overlap between the maps showing high HIV prevalence in Africa (particularly amongst women and adolescents girls) and those showing cases of female genital schistosomiasis. A complex interplay of biological, social and cultural factors means that young women are particularly vulnerable to HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. Gender norms also shape exposure to urogenital schistosomiasis, with women being particularly responsible for activities involving water in many communities – like washing, cleaning, and collecting water.

What to do?

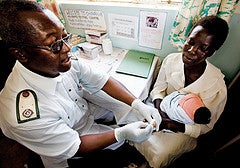

Several tens of millions of praziquantel tablets are now donated each year for mass drug administration campaigns as a cost-effective method to protect people from urogenital schistosomiasis. Hotez argues that by preventing female genital schistosomiasis in sexually active women, we have an innovative and timely opportunity to reduce, and likely much reduce, HIV transmission throughout many rural areas of sub-Saharan Africa.

The lack of action to date on urogenital schistosomiasis clearly illustrates the importance of new partnerships and new approaches to scaling up strategies. To make progress in this area, we need joint action between the HIV, maternal, sexual and reproductive health and neglected tropical disease communities. Health workers and communities need more information on the multiple impacts of urogenital schistosomiasis and how it can be treated. A meeting in South Africa later in this month should start this dialogue.