The Alma-Ata Declaration and primary health care

The ground-breaking 1978 Alma-Ata Declaration emphasized the central role of primary health care in ensuring equitable access to high quality services, declaring that:

“Primary health care is essential health care based on practical, scientifically sound and socially acceptable methods and technology made universally accessible to individuals and families in the community through their full participation and at a cost that the community and country can afford to maintain at every stage of their development in the spirit of self-reliance and self-determination. It forms an integral part both of the country’s health system, of which it is the central function and main focus, and of the overall social and economic development of the community. It is the first level of contact of individuals, the family and community with the national health system bringing health care as close as possible to where people live and work, and constitutes the first element of a continuing health care process.”

Since then, many countries have struggled to integrate a variety of high quality services into their primary health care systems. Researchers have attempted to identify best practices and promising strategies for achieving the goals set forth in the Alma-Ata Declaration, but more work is needed.

Maternal, newborn and child health integration

In a 2008 article published in The Lancet, Bhutta and colleagues systematically reviewed interventions and strategies for integrating maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH) services into primary care. Despite the limited evidence in this area, the authors were able to examine a number of MNCH interventions that can be integrated into primary care settings and categorize the interventions according to level of recommendation:

|

Universal recommendation |

Situational recommendation |

| Referral for skilled care including oxytocic use and active management of third stage of labor for prevention of postpartum hemorrhage; cesarean as indicated (first-level facilities) | Possible basic neonatal resuscitation strategies for health facilities and in community settings |

| Antibiotics for preterm, premature rupture of membranes (first-level facilities) | Community treatment of infections, including antibiotics for pneumonia and sepsis |

| Continuity of care between trained traditional birth attendants, midwives and doctors | Training traditional birth attendants for basic newborn care and referrals to health system |

| Magnesium sulfate for pre-eclampsia (first-level referral facilities) | Calcium supplementation during pregnancy (universal in populations with low calcium intake) |

| Maternal mental health interventions | Lose-dose aspirin in pregnancy (for at risk women) |

| Antenatal steroids for those at risk of preterm births (first-level facilities) | Continued care and rehabilitation of undernourished children |

| Early child development interventions | Insecticide-treated bed nets |

| Road traffic injury or accident prevention strategies | Prevention and treatment of severe acute malnutrition in affected children |

| iPTi and iPT for malaria prevention | |

| Kangaroo mother care |

Many of the MNCH interventions were executed with the use of trained community health workers (CHWs), resulting in significant reductions in perinatal and neonatal mortality and maternal morbidity. Some of the most effective and feasible strategies identified involved the distribution of essential medicines such as magnesium sulfate for pre-eclampsia/eclampsia and oxytocics for preventing hemorrhage.

Barriers to implementation

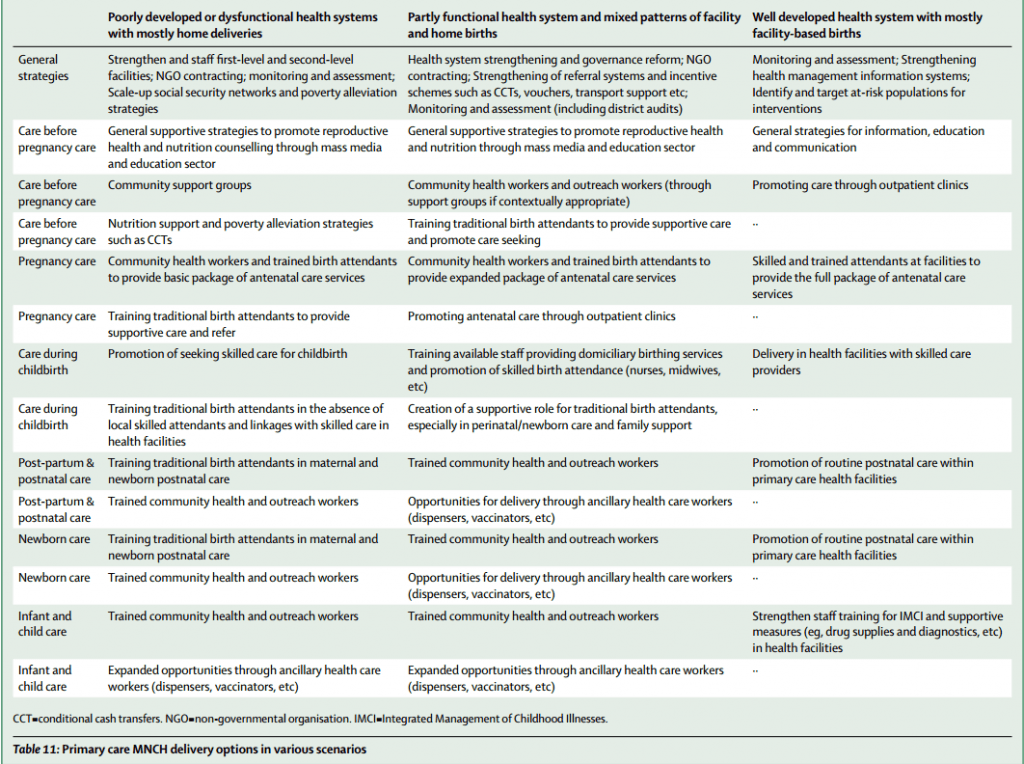

Implementing these strategies requires numerous resources including a strong, well-trained health workforce, physical infrastructure, essential medicines, equipment and efficient referral systems. Acknowledging the diversity of global health systems’ capacity to deliver these interventions, Bhutta and colleagues offered different ways to integrate MNCH services into primary health care based on the particular context:

The authors also highlighted four key barriers to delivering MNCH interventions at scale:

- Lack of global consensus on a minimum set of MNCH interventions

- Lack of attention to community-level demand for care

- Shortage of trained staff and hesitation to use task-shifting strategies

- Failure to allocate resources to primary care facilities including supervision and strong links to CHWs

Engaging communities

Integrating MNCH services into primary health care can be an effective strategy for reducing health inequities—particularly socioeconomic and geographic disparities—by delivering care at the community level. As suggested in the Alma-Ata Declaration, community involvement in the design, implementation and evaluation of integrated primary care interventions is crucial for ensuring that MNCH programs are successful.

Are you interested in learning more about community health?

Tune into the Institutionalizing Community Health Conference (ICHC) in Johannesburg, South Africa from 27 – 30 March by watching the live-stream.

Attending the conference? Join us at the following MHTF-supported panels:

Session 26: Community empowerment and gender

Session 30: Building national capacity and demand for implementation research to take forward the community health agenda

Session 32: Selected topics in implementation research for community-based service delivery

Graphic: Bhutta et al. Interventions to address maternal, newborn and child survival: What difference can integrated primary health care strategies make? The Lancet, 2008.

—

Learn more about the Alma-Ata Declaration.

Enjoy an interview with Dr. Zulfiqar Bhutta from the MHTF’s Global Leaders in Maternal and Newborn Health blog series.

Read more about community-based strategies for improving maternal health.