Twenty percent of the 800 preventable maternal deaths occurring globally every day are from India. Research has amply demonstrated that maternal health service utilization is lowest among tribal groups than any other community in India due to the long distances from health facilities or their unavailability, cultural barriers, low educational level of women, and economic inequalities. During 2017-2019, 62 women died due to pregnancy and childbirth complications in Nandurbar, a tribal district in Maharashtra, a state that contributes to 15% of India’s GDP. Multiple pregnancies in younger ages weakening health and nutrition of mothers is a deep-rooted problem necessary to address when combating maternal mortality (our data show that 31% of mothers < 25 years of age conceived twice or more). While improving infrastructure and bridging the access-gap are essential, cultural barriers cannot be ignored. Studies show that while the concept of deities and their effect on health is widespread among tribal communities, their acceptance of modern healthcare depends on its availability and accessibility. The ideal healthcare model improves their awareness and reduces their inhibitions to attend care centres, without ignoring their long-standing healing practices. Indeed, we need a co-existence of modern public health interventions with traditional thought, not necessarily a collaboration and definitely not a conflict. Tribal communities will need treatment alternatives to help evolve their decision-making on care-seeking. A true co-existence requires the intervention to enter their daily lives and there, technology plays a key role. A health program relying on the power of local community workers empowered with point-of-care devices that can assess mothers’ health within the comforts of their homes and relay the results to doctors is a potential model. The CareMother technology, being piloted in Nandurbar since July 2018, is a pertinent example.

CareMother consists of a portable diagnostic kit used by a health worker for home-based point-of-care antenatal tests, and a smartphone application with a ‘decision-support tool (DST)’ for detecting high-risk pregnancies, delivering specific counselling messages and referral to doctors via real-time results for prompt clinical decisions. The trained frontline workers can deliver personalized pregnancy care through the DST that fetches data from doorstep antenatal tests and classifies risk and further course of action.

Health workers received training on the kit and application, but were initially challenged by household cultural barriers based on prevailing societal views towards women. For instance, communities looked upon women carrying medical kits and phones as ‘urbane’ and ‘trying to teach medicine’ to the elderly and experienced people, which was not a favourable impression for newly inducted workers. Grandparents (in-laws) resisted the ‘exposure’ of mothers to health workers because women did not have direct interactions with visitors in these communities as a societal norm (in spite of inducting female health workers).

Therefore, the CareMother team had renewed detailed discussions with the village heads (some were educated till primary school) with whom they had introductory meetings at the start of the program. These discussions focused on the credibility of the hospital affiliated with the program (located in a nearby city) and the operational and health benefits to mothers due to the mobile care model. After the village heads were convinced, they explained potential benefits to the communities, and the families gradually allowed home visits. Over six months, mothers began to accept the services and even wait for health workers on the assigned days and exhorted other women to do so as well. The program also leveraged their husbands (as evident in research) knowing that they migrated to adjacent cities for jobs and had exposure to the value of antenatal health practices. The continued dialogue with mothers transformed the impression of the health workers. The communities began to perceive them ‘like doctors’.

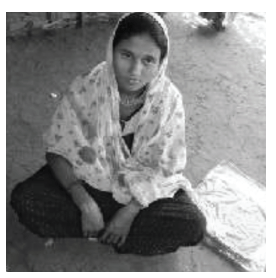

I am Sujatha (name changed), about 25 years old. I am a resident of Chanwaipada and I am a mother of two and pregnant for the third time. This time, during my pregnancy, ASHA didi came to my home with a kit and she asked me a few details and entered the same into a mobile phone. At the end, she clicked my photo and that made me feel very good. Then she opened the box and pricked my blood for doing some tests. She later explained to me that my blood pressure is high and I had to visit the doctor. She also explained my complete health status, for which I had to travel 3 hours by walk and 20 km by local transport, otherwise. Then I explained her that it will be tough for me to visit the doctor immediately as my husband is away and I had to take care of my children till he returns back. She then gave me some medicine for headache, advised me on taking a balanced diet and not to take too much salt, and asked me to monitor my food intake. I felt like I actually consulted a doctor and she has transformed my initial thoughts on the same.

A lot more needs to be done as there are other perceptions that reduce visits to the facilities such as fear of injections, the ‘harmful and needless’ episiotomy cuts after deliveries, the unfavoured postnatal stay of 2-3 days ‘exposing the mother to other communities during this sensitive time’ and causing a loss of daily wages, and the strongly held belief that the delivering woman is supposed to ‘clean the place where she delivers, unassisted’ (not possible in a clinic). However, the communities are open to clinic-visits when any illnesses become serious or a traditional healing practice causes an infection. This indicates their willingness to accept a co-existence of modern medicine with traditional norms.

To conclude, CareMother ‘hand-held’ a tribal culture to the reception of modern maternal care through a continued dialogue with mothers via home visits and involvement of village heads and husbands. Technology bridged the access gaps to facilitate this process via point-of-care tests and a decision-support tool linking with doctors. Maternal care interventions in tribal communities should strongly consider the use of technology and become as community-entrenched as possible for creating a viable service demand.

Since 2015, the CareMother program has registered 30,000+ pregnancies and identified 12,000+ high-risk pregnancies via 260 community health workers across ten states of India, in rural, urban and tribal areas, collaborating with 15+ Government, non-profit and corporate (CSR) partners. Nandurbar is one of the three tribal areas in India where CareMother is being implemented since August 2018. An independent third-party evaluation of this program is being conducted by the Society of Community Health Oriented Operational Links (SCHOOL), a research organization based in New Delhi, India. The evaluation commenced in June 2019 and a report will be prepared by November 2019.

Acknowledgements: This program is supported by Larsen & Toubro Technology Services and Savitribai Phule Mahila Ekatma Samaj Mandal (implementing partner). We would like to show our gratitude to Dr. Pratibha Phatak, Project Director, Hedgewar Hospital, Aurangabad, India for her valuable guidance throughout the program.

Notes on the Authors: Ameya Bondre (Head: Clinical Research and Development), Anjana Donakonda (Program Manager), Pritee Dehukar(Operations Manager), Avinash Joshi (Software Development Lead), Aditya Kulkarni (Managing Director), Shantanu Pathak (Executive Director) at CareNX Innovations, Mumbai, India